15

FEBRUARY, 2025

PFAS: The Hidden Chemical Crisis in Africa’s Waters

By: Ashirafu Miiro

Ashirafu Miiro is a participant in an exchange programme at the Institute for Water Research (IWR) representing Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda, for six months from November 2023 to May 2025. As a Masters candidate with aspirations for a PhD, his research focuses on analytical and environmental chemistry, particularly in detecting water contaminants such as persistent organic pollutants (POPs). He intends to leverage this expertise to develop purification technology for Africa’s vulnerable water systems.

Ashirafu Miiro: The search for PFAS

PFAS? What’s PFAS?

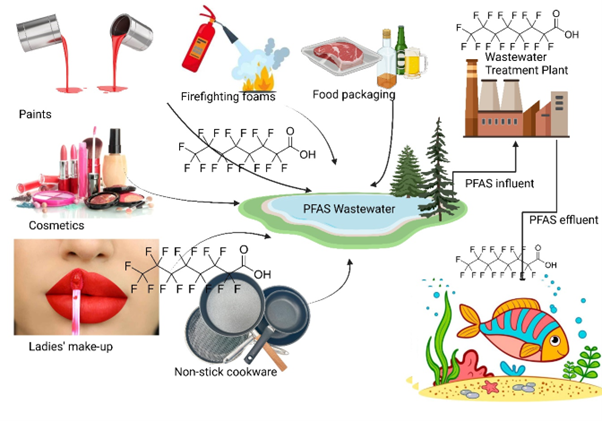

That’s a short form for “per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.” These are called “forever chemicals” because they never break down, remaining in the environment for years. Today, PFAS are silently polluting Africa’s rivers and lakes, damaging water quality, wildlife, and human health. They are found in everyday items—from non-stick pans and water-resistant clothing to pesticides and fertilizers—making their way into our environment in many unexpected ways.

Where are they?

PFAS enter our waters in several different ways. Factories and outdated wastewater treatment plants1 are major sources. When these facilities discharge PFAS into rivers—such as South Africa’s Vaal, and Kenya’s Nairobi—the chemicals spread quickly through entire ecosystems2. One of the most troubling hotspots3 is Lake Victoria, Africa’s largest lake. Every year, more and more PFAS pollute this massive body of water, which feeds the Nile and supports millions of people. Similar problems are also appearing in rivers across the continent, including parts of the Eastern Cape. As PFAS travel downstream, they gather in sediments and aquatic4 life, creating long-lasting reservoirs of contamination5 that pose a long-term risk.

Lake Victoria

Why should we care?

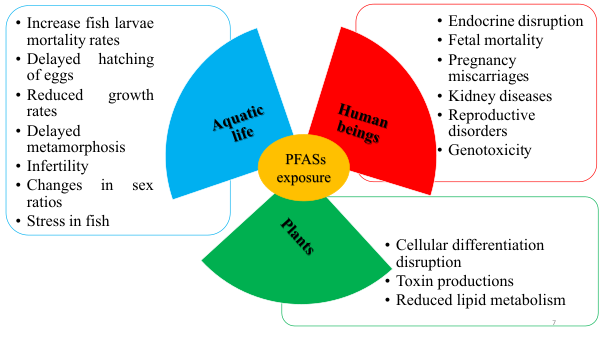

PFAS collect in fish and other organisms. When people eat contaminated fish, they unknowingly eat these harmful chemicals. Over time, this can lead to serious health issues, such as cancer, kidney and liver diseases, and reproductive problems. In communities where fishing is the main source of food and income, the effects can be particularly serious. Because PFAS degrade so slowly, the chemicals remain in the ecosystem, continuously cycling through the food chain. This repeated poisoning upsets the balance of aquatic life and leads to a decline in biodiversity and to the overall health of our water systems—and us!

The good news?

There are ways to fight back against PFAS pollution. First, by stronger regulations and enforcing stricter limits on industrial discharges, African governments can reduce the amount of PFAS entering our waters. Upgrading wastewater treatment plants is another critical step.

New technologies—such as advanced oxidation6 processes and adsorption7 methods—have shown promise in removing PFAS from effluents8 before they reach natural water bodies.

Raising public awareness is equally important. When communities understand the risks associated with PFAS, they are better equipped to demand cleaner water and support initiatives aimed at reducing pollution. When governments, industries, and researchers work together, they can encourage the development of innovative solutions designed for local conditions.

By understanding the sources and impacts of PFAS, we can take meaningful action to protect Africa’s water resources. Dealing with this hidden crisis is vital for human health and also to preserve the rich biodiversity and ecological balance of our rivers and lakes.

Let’s make a united effort and increase our watchfulness to make it possible to safeguard our water for future generations.

Ashirafu Miiro (6th from left) joined River Rescue to clean up the Evans Street site

Helpful Words

- Wastewater treatment plants – Systems that clean water polluted by sewage, industrial waste, agricultural chemicals, and other contaminants.

- Ecosystem – A community of living things (plants, animals, and microorganisms) interacting with their environment (such as water, soil, and weather).

- Hotspot – An area where pollution is especially high or where problems are more severe.

- Aquatic life – All the living organisms that live in water, including fish, plants, and insects.

- Contamination – Pollution; the presence of harmful substances (like chemicals or waste) in water that can make it unsafe for living things.

- Oxidation – A chemical process that uses air or specific chemicals to break down pollutants in water, thereby cleaning it.

- Adsorption – A process where molecules of harmful substances stick to a cleaning material, helping to remove the pollution from the water.

- Effluent – Water that has been discharged from a wastewater treatment plant, which may still contain some pollution.

- Persistent – Describes chemicals that do not break down easily in the environment and remain for a long time.